Inside Architect Wayne Turett’s Passive Home: A 'Living Laboratory' of Energy Efficiency

Story at a Glance

- Architect Wayne designed his own home on Long Island using passive building methods, including triple-glazed windows, dense insulation, and an energy-recovery ventilation system.

- Turett’s project emphasizes the importance of airtight construction, proper sealing, and attention to detail, especially in window installation and insulation.

- The fully electric home features a heat pump HVAC, water heater, and induction cooking, with plans to install flexible solar panels to pursue net-zero energy goals.

- Despite higher initial costs, Turett advocates for the long-term benefits and environmental impact of passive building practices, encouraging incremental improvements over perfection.

Among the cottages and traditional homes of Shelter Island, N.Y., architect Wayne Turett’s ultra-high-performance home fits into its historic surroundings, with a slightly more modern edge. Built to rigorous passive building standards, the 2,400-square-foot structure functions as his personal laboratory, where Turett tests how airtight systems, sustainable materials, and design choices perform in real-world conditions.

Turett, principal of the Turett Collaborative in New York City, designed the home with a passive-first approach to experience firsthand how energy-efficient technologies perform. The goal is to consume about 90% less heating energy than existing homes and 75% less than average new construction.

“The whole idea of doing this to passive house standards comes from my trip to Berlin more than 10 years ago, staying at a friend’s house—another architect,” he says. “I always thought Passive House was basically a bunker with a couple of small windows. But one of the things that struck me was the amount of glass. The windows were so large. It was so beautiful. The light coming in was amazing.”

After three years of research and planning, Turett purchased a lot in the village of Greenport and began using passive strategies to build his own house. “I didn’t know how daunting it would be, or how hard it would be, but I had always been inching up to [the passive approach] in our practice,” he said, noting how his firm always designed well ahead of local codes.

Site & Design Considerations

The property is a long, narrow lot, about 210 feet by 70 feet, which influenced the home’s design and orientation.

Making the house two stories and placing the main living areas upstairs became evident as Turett spent more time on the site, going so far as climbing a ladder to confirm the views.

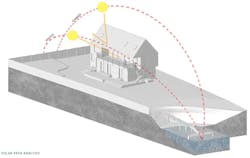

Passive principles guided the home’s orientation to the south, to maximize passive heating and cooling, but the tight lot created limitations.

“Because the lot was long and narrow, I was able to orient the house more to the south,” he says, “but not fully.”

The strategic use of overhangs to block summer sun, triple-glazed windows, dense-pack cellulose insulation, and an energy-recovery ventilation (ERV) system picked up the slack, working to further minimize heating and cooling needs.

Aesthetic choices balanced Turett’s modernist taste with local historic preservation requirements. His initial sketches were more contemporary, featuring flat roofs and a box-like form, he says. But he modified the design to a peaked aluminum roof evoking a barn and used ship-lapped grey cedar to satisfy the historic committee; he then stripped-down detailing (no shutters, corner boards, or extraneous trim) to satisfy his own contemporary preferences.

Construction & Challenges

Turett acted as his own construction manager, working closely with Jared Loveless of Vector East, a local design-build contractor.

“He's an engineer, and without him, I probably couldn't have done it as well as I did,” he said. “It came down to two things: the design, architecturally and aesthetically, and the design, thermally and passively. He was definitely a valued consultant.”

Finding tradespeople familiar with Passive House principles, however, proved to be more difficult.

“Contractors are pretty much set in their ways,” says Turett, explaining that many were unfamiliar with methods like dense pack cellulose, which must be filled to a certain pressure. The home’s tightly sealed envelope also required sheathing to be taped to form a tight air barrier, which is key to the energy efficiency of the house.

“It's certainly a lot easier to do a passive house if you have a very simple box,” Turett says. “The more surface area you have, the more difficult it is, and the more insulation you'll need. The envelope has to be completely sealed.”

Systems & Choices

The home itself is fully electric, with a three-ton heat pump HVAC, heat pump water heater, and heat pump dryer. And while New York still relies on fossil fuels for roughly 46% of electricity generation, according to the U.S. Energy Information Association, Passive House standards encourage all-electric buildings as a way to eventually shift toward entirely renewable energy. “I don’t love the idea of flames in my house,” Turett says. “But going all-electric, I don’t think is a compromise at all. I have a three-ton heat pump, and it's been great. It’s super quiet, and I'm never uncomfortable. It works really well.”

Cooking follows the same principle. Induction has replaced gas, and Turett notes it outperforms his city gas stove: “You want to boil water, and it’s super-fast. And there’s a lot less pollutants that are coming into the house.”

Passive strategies are reinforced through the building envelope and ventilation. Triple-glazed windows, dense insulation, and an ERV system ensure constant fresh, filtered air. Blower door tests confirmed 0.9 air changes per hour, which, Turett notes, is just shy of formal Passive House certification standards.

I toyed with [certification] briefly, but it’s fairly expensive," Turett explains. "To spend another $6,000 or $7,000 to certify it would have been out of the price range."

Solar panels were initially postponed, but for aesthetic considerations. “I have a standing seam roof, and I never wanted those big, clumsy panels on the roof,” Turett says.

But he recently learned that Sunflare, based in La Verne, Calif., had introduced flexible solar panels that nestle between metal standing seams, and so he put an installation proposal together for the historic committee, which earned quick approval.

He plans to do the install later this fall. “I still don't know if it's going to work (to help achieve net-zero),” he says, “but, it's part of the proof of concept that I want to see. My house is a living laboratory.”

Performance Results

That commitment to experimentation has already delivered measurable results.

A Home Energy Rating System (HERS) analysis estimates annual heating and cooling costs at just over $1,700 for the 2,400-square-foot house. By comparison, a much smaller 900-square-foot New York City apartment can spend nearly as much, roughly $1,400 a year, on just cooling and lighting alone.

Overall, Turett's home exceeds its HERS reference model by an estimated $3,600 in annual energy savings. And his actual electricity bills average between $110 and $120 per month, covering heating, cooling, domestic hot water, laundry, and even charging an electric car.

Beyond the numbers, Turett notes the home is unexpectedly quiet. "Because it's so sealed up, so insulated, and with triple-glazed windows, you don't hear anything outside," he says. "But you start to notice things you wouldn't normally hear in a conventional house, like the refrigerator compressor. Still, the house is super quiet."

The ERV also keeps air fresh by continuously filtering and exchanging indoor air. "Your house air is a lot fresher. It's like opening a window, but without the energy loss," Turett says, noting that the system runs efficiently enough to operate 24/7.

After three years from conception to completion, and some time living in the home, Turett considers a few things he might do differently.

"I would do less rigid polyiso insulation and replace that with mineral wool and dense-packed cellulose," he says, reflecting on material choices that would help improve performance.

He's also tested materials and applications with success. The primary bathroom features wood flooring and plaster walls instead of tile, including in the shower, which has held up well.

"It's proof-of-concept,” he says. “A bathroom can look great with white Venetian plaster walls. I would encourage clients to go that way."

And while the overall project cost more than traditional construction, Turett says the investment is worthwhile.

“It doesn't have to cost a fortune more,” he says. “There's a bump. But the bump pays off.”

Client Interest, Builder Advice

Turett says some clients have reached out after hearing about his home project, seeking energy-efficient homes for themselves, but that others are more drawn to his firm's contemporary aesthetic.

"A lot of these homes are multi millions of dollars, and to save another hundred bucks on their power bill is probably not high on their list," he says. "But the thing that gets them usually is the idea that the air quality is so good inside the house. They perk up and listen."

For builders pursuing passive construction, Turett says execution is key. "You need to pay a little bit more attention to the details before the trim goes on. You have to make sure that the windows are sealed up, that the flashing is correct, that the air barrier is taped and rolled properly,” he says. “Traditional building had more leeway. But with Passive House, these things need to be done properly."

Insulation and mechanical contractors are most important, he says, followed by making sure window specifications live up to air change and infiltration standards.

But despite going to great lengths to conceive, design and execute the passive approach in his own home, Turett keeps his overall advice quite practical. "You don't have to do the whole nine yards,” he says. “Certainly, the more the better. But it's not one or none. Do what you can. Anything you do is helpful."

Project Credits:

Architect/Construction Manager: Wayne Turett, Turett Collective

Engineering Consultant: Jared Loveless, Vector East

Air Barrier/House Wrap: Solitex Mento

Adhesive Tape: Tescon Vana

Triple-Glazed Windows/Doors: Bildau & Bussmann (via Eco Supply)

ERV: Zehnder America

Flexible Solar Panels: Sunflare

Cooktop: Samsung Induction

Standing Seam Roof: Atas International

Photography: Liz Glasgow Studios

In Case You Missed It...

About the Author

Pauline Hammerbeck

Pauline Hammerbeck is the editor of Custom Builder, the leading business media brand for custom builders and their architectural and design partners. She also serves as a senior editor for Pro Builder, where she directs products coverage and the brand's MVP Product Awards. With experience across the built environment - in architecture, real estate, retail, and design - Pauline brings a broad perspective to her work. Reach her at [email protected].